1. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard» URL:. https://covid19.who.int and «COVID-19 vaccinestechnicaldocuments» 30, November, 2021.

2. Chung MK, Karnik S, Saef J, Bergmann C, Barnard J, Lederman MM, Tilton J, Cheng F, Harding CV, Young JB, Mehta N, Cameron SJ, McCrae KR, Schmaier AH, Smith JD, Kalra A, Gebreselassie SK, Thomas G, Hawkins ES, Svensson LG. SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2: The biology and clinical data settling the ARB and ACEI controversy. EBioMedicine. 2020 Aug;58:102907. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102907. Epub 2020 Aug 6. PMID: 32771682; PMCID: PMC7415847.

3. Whittaker GR. SARS-CoV-2 spike and its adaptable furin cleavage site. Lancet Microbe. 2021 Oct;2(10):e488-e489. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00174-9. Epub 2021 Aug 6. PMID: 34396356; PMCID: PMC8346238.

4. Ge XY, Li JL, Yang XL, Chmura AA, Zhu G, Epstein JH, Mazet JK, Hu B, Zhang W, Peng C, Zhang YJ, Luo CM, Tan B, Wang N, Zhu Y, Crameri G, Zhang SY, Wang LF, Daszak P, Shi ZL. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2013 Nov 28;503(7477):535-8. doi: 10.1038/nature12711. Epub 2013 Oct 30. PMID: 24172901; PMCID: PMC5389864.

5. Zajac V, Matelova L, Liskova A, Mego M, Holec V, Adamcikova Z, Stevurkova V, Shahum A, Krcmery V. Confirmation of HIV-like sequences in respiratory tract bacteria of Cambodian and Kenyan HIVpositive pediatric patients. Med Sci Monit. 2011 Feb 25;17(3):CR154-8. doi: 10.12659/msm.881449. PMID: 21358602; PMCID: PMC3524724.

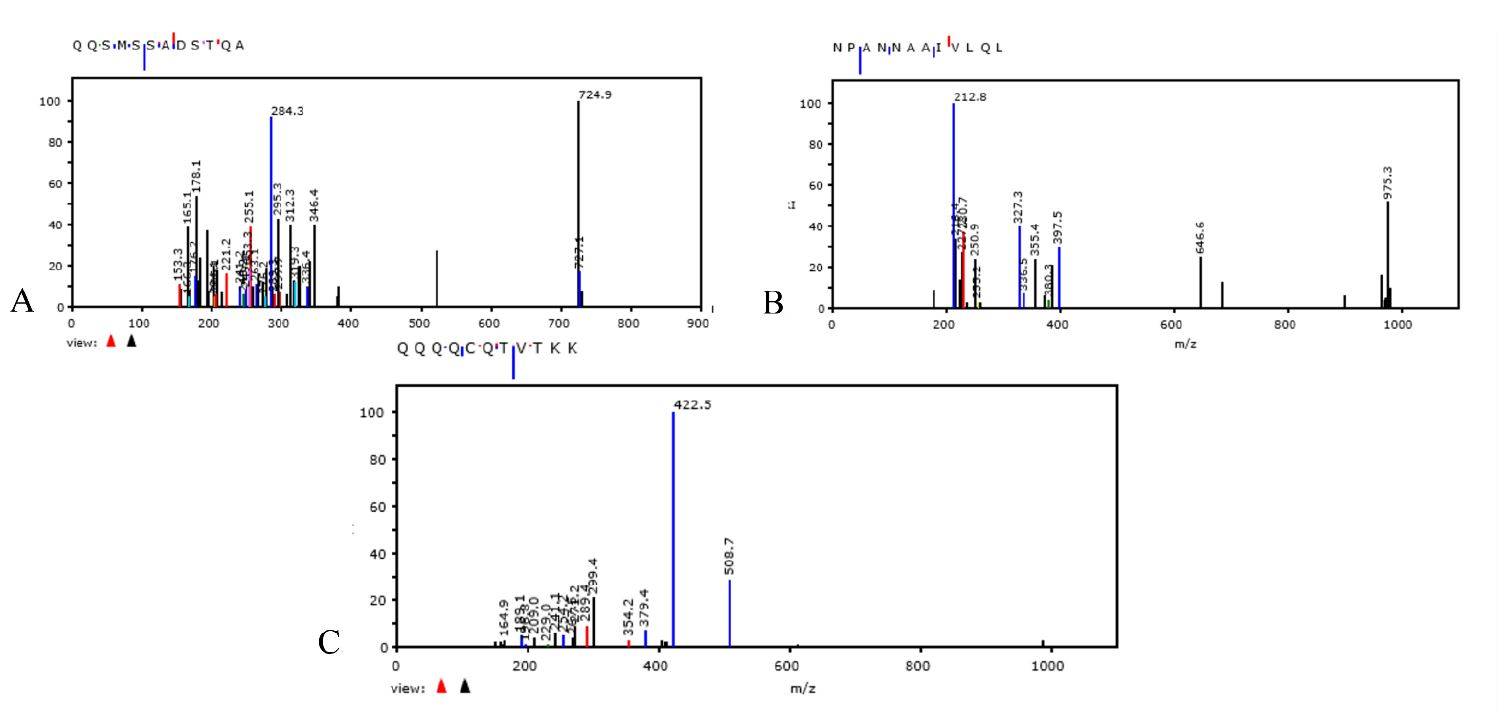

6. Brogna C, Cristoni S, Petrillo M, Querci M, Piazza O, Van den Eede G. Toxin-like peptides in plasma, urine and faecal samples from COVID-19 patients. F1000Res. 2021 Jul 8;10:550. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.54306.2. PMID: 35106136; PMCID: PMC8772524.

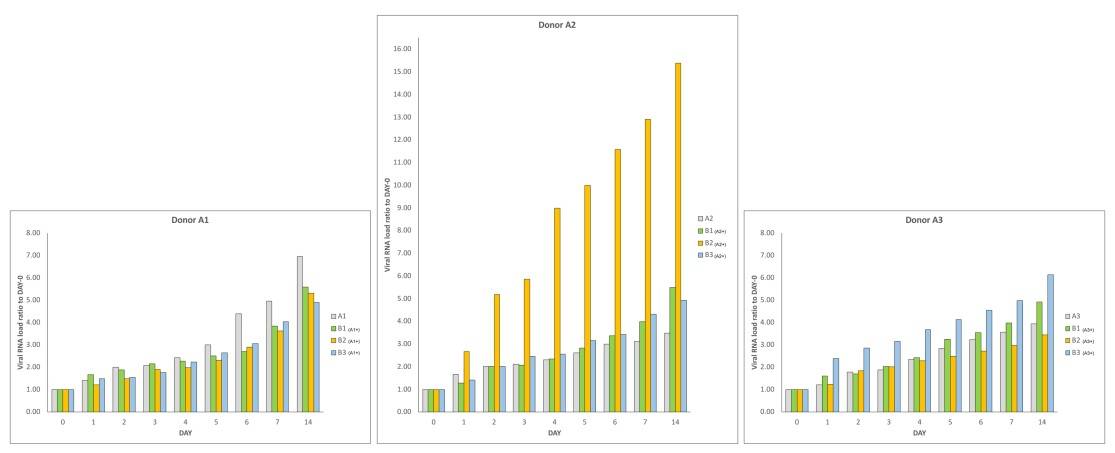

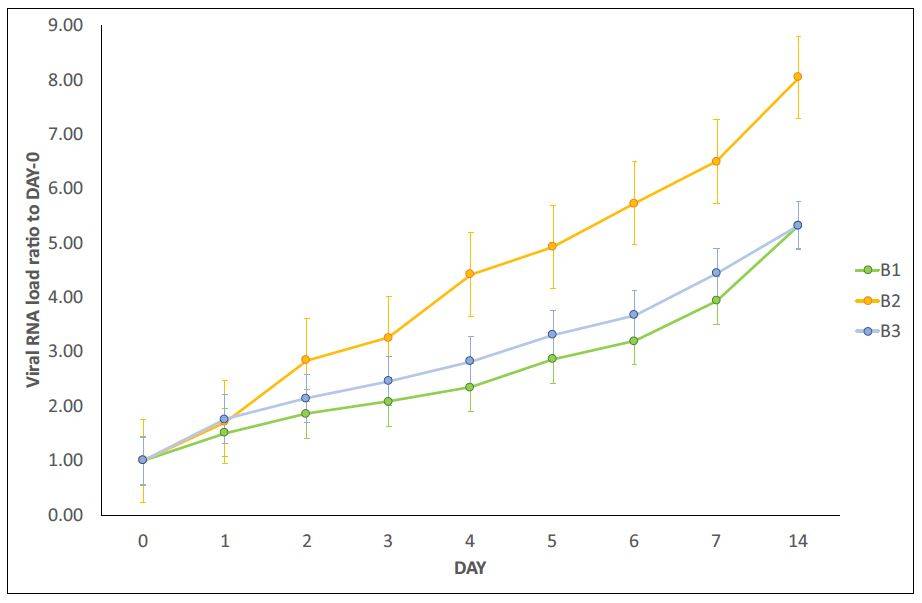

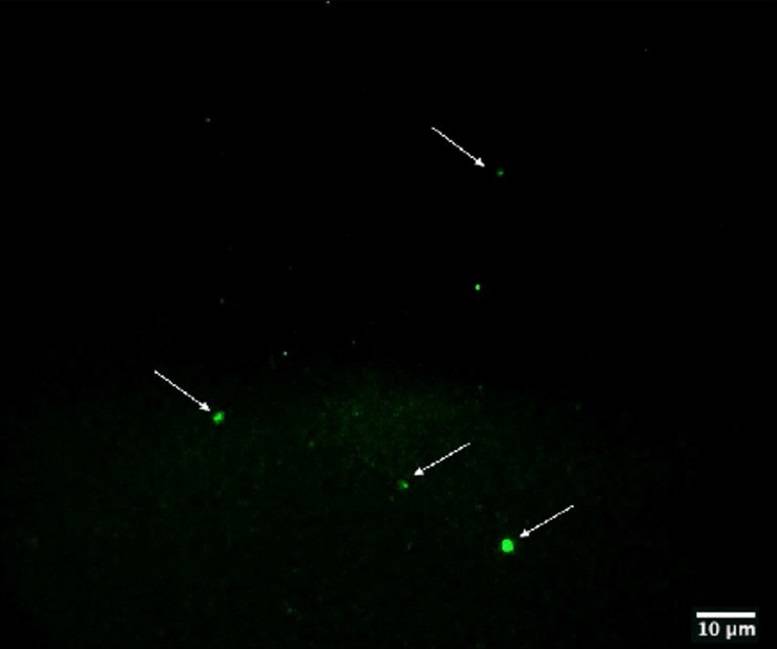

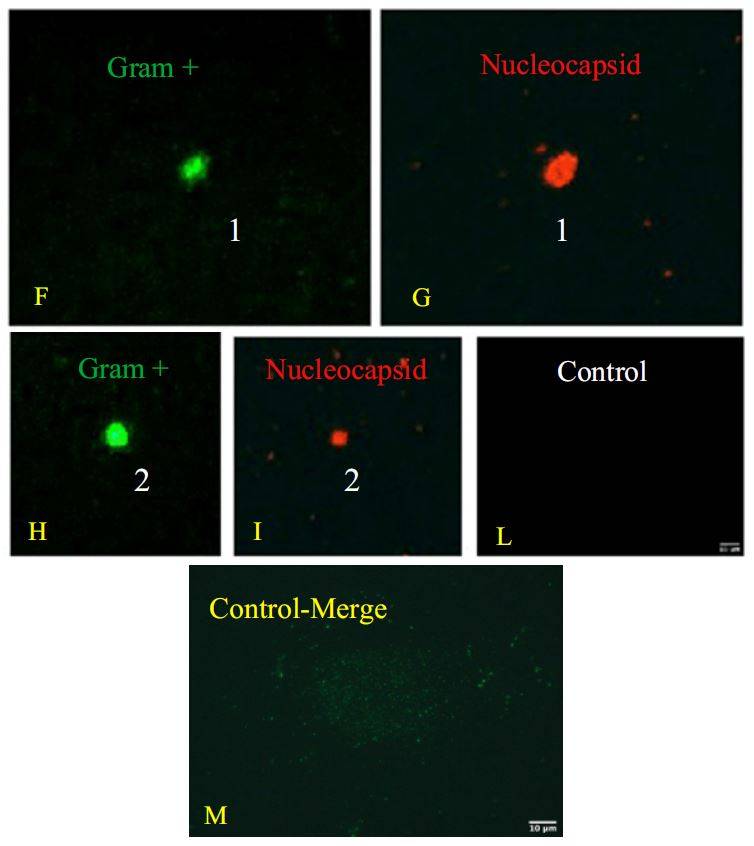

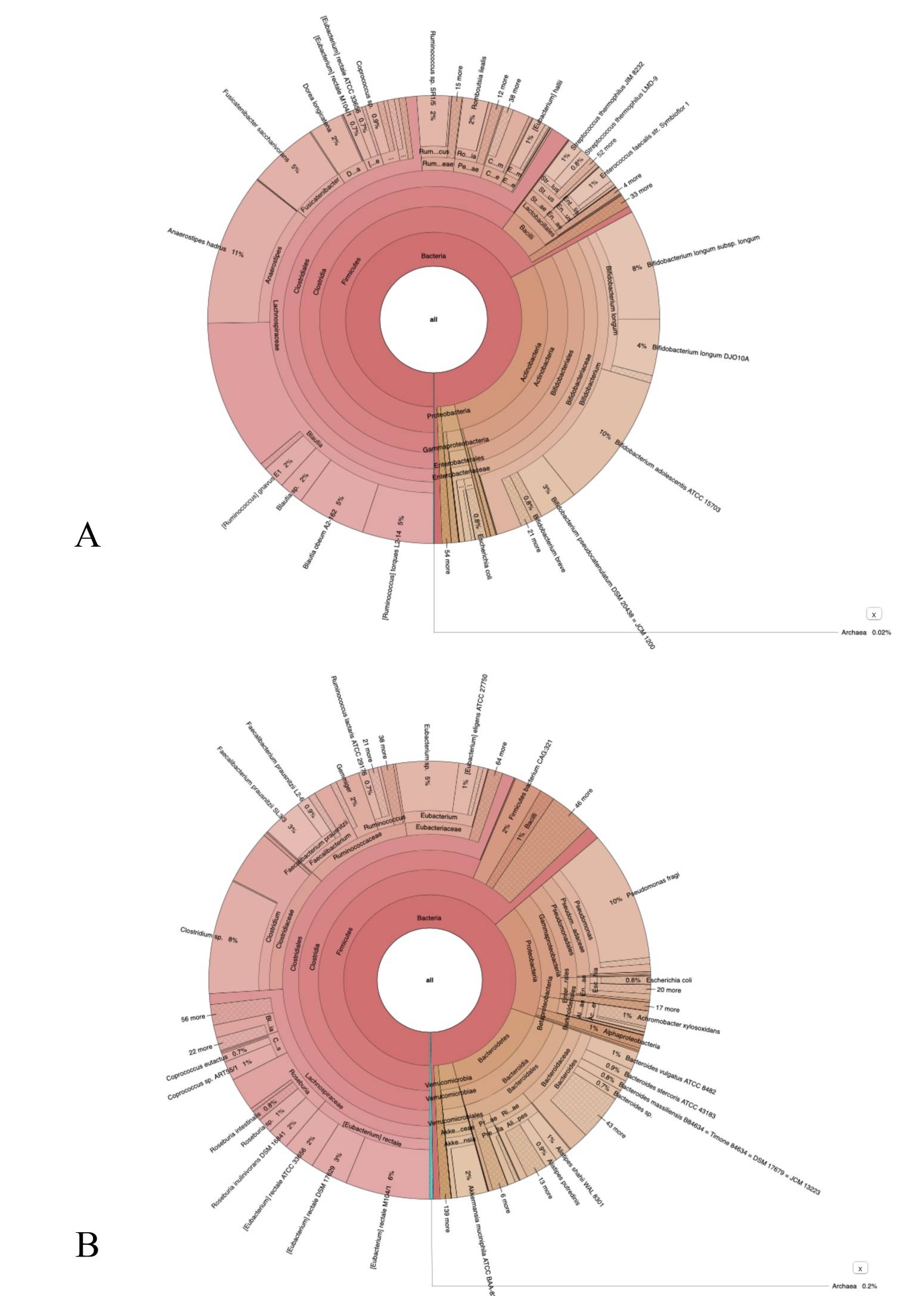

7. Petrillo M, Brogna C, Cristoni S, Querci M, Piazza O, Van den Eede G. Increase of SARS-CoV-2 RNA load in faecal samples prompts for rethinking of SARS-CoV-2 biology and COVID-19 epidemiology. F1000Res. 2021 May 11;10:370. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.52540.3. PMID: 34336189; PMCID: PMC8283343.

8. www.ec.europa,eu Url: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/news/covid-19-and-our-gut-microbiome-evidenceclose- relationship 20 october 2021

9. Wang H, Wang H, Sun Y, Ren Z, Zhu W, Li A, Cui G. Potential Associations Between Microbiome and COVID-19. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021 Dec22;8:785496. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.785496. PMID: 35004750; PMCID: PMC8727742 10. Haiminen N, Utro F, Seabolt E, Parida L. Functional profiling of COVID-19 respiratory tract

microbiomes. Sci Rep. 2021 Mar 19;11(1):6433. doi:

10.1038/s41598-021-85750-0. PMID: 33742096; PMCID: PMC7979704.

11. Honarmand Ebrahimi K. SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein-binding proteins expressed by upper respiratory tract bacteria may prevent severe viral infection. FEBS Lett. 2020 Jun;594(11):1651-1660. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13845. PMID: 32449939; PMCID: PMC7280584.

12. Dragelj J, Mroginski MA, Ebrahimi KH. Hidden in Plain Sight: Natural Products of Commensal Microbiota as an Environmental Selection Pressure for the Rise of New Variants of SARS-CoV-2. Chembiochem. 2021 Oct 13;22(20):2946-2950. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202100346. Epub 2021 Jul 26. PMID: 34265150; PMCID: PMC8427076.

13. Podlacha M, Grabowski Ł, Kosznik-Kawśnicka K, Zdrojewska K, Stasiłojć M, Węgrzyn G, Węgrzyn A. Interactions of Bacteriophages with Animal and Human Organisms-Safety Issues in the Light of Phage Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Aug 19;22(16):8937. doi: 10.3390/ijms22168937. PMID: 34445641; PMCID: PMC8396182.

14. Bertrand K. Survival of exfoliated epithelial cells: a delicate balance between anoikis and apoptosis. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:534139. doi: 10.1155/2011/534139. Epub 2011 Oct 27. PMID: 22131811; PMCID: PMC3205804.

15. Ondov BD, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. Interactive metagenomic visualization in a Web browser. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011 Sep 30;12:385. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-385. PMID: 21961884; PMCID: PMC3190407.

16. Cristoni S, Rubini S, Bernardi LR. Development and applications of surface-activated chemical ionization. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2007 Sep-Oct;26(5):645-56. doi: 10.1002/mas.20143. PMID: 17471584.

17. Zajac V, Mego M, Martinický D, Stevurková V, Cierniková S, Ujházy E, Gajdosík A, Gajdosíková A. Testing of bacteria isolated from HIV/AIDS patients in experimental models. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2006 Dec;27 Suppl 2:61-4. PMID: 17159781.

18. Xu H, Wang X, Veazey RS. Mucosal immunology of HIV infection. Immunol Rev. 2013 Jul;254(1):10-33. doi: 10.1111/imr.12072. PMID: 23772612; PMCID: PMC3693769.

19. Diallo B, Sissoko D, Loman NJ, Bah HA, Bah H, Worrell MC, Conde LS, Sacko R, Mesfin S, Loua A, Kalonda JK, Erondu NA, Dahl BA, Handrick S, Goodfellow I, Meredith LW, Cotten M, Jah U, Guetiya Wadoum RE, Rollin P, Magassouba N, Malvy D, Anglaret X, Carroll MW, Aylward RB, Djingarey MH, Diarra A, Formenty P, Keïta S, Günther S, Rambaut A, Duraffour S. Resurgence of Ebola Virus Disease in Guinea Linked to a Survivor With Virus Persistence in Seminal Fluid for More Than 500 Days. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Nov 15;63(10):1353-1356. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw601. Epub 2016 Sep 1. PMID: 27585800;

PMCID: PMC5091350.

20. Cheung KS, Hung IFN, Chan PPY, Lung KC, Tso E, Liu R, Ng YY, Chu MY, Chung TWH, Tam AR, Yip CCY, Leung KH, Fung AY, Zhang RR, Lin Y, Cheng HM, Zhang AJX, To KKW, Chan KH, Yuen KY, Leung WK. Gastrointestinal Manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Virus Load in Fecal Samples From a Hong Kong Cohort: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jul;159(1):81-95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.065. Epub 2020 Apr 3. PMID: 32251668; PMCID: PMC7194936.

21. Brogna B, Brogna C, Petrillo M, Conte AM, Benincasa G, Montano L, Piscopo M. SARS-CoV-2 Detection in Fecal Sample from a Patient with Typical Findings of COVID-19 Pneumonia on CT but Negative to Multiple SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR Tests on Oropharyngeal and Nasopharyngeal Swab Samples. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021 Mar 20;57(3):290. doi: 10.3390/medicina57030290. PMID: 33804646; PMCID: PMC8003654.

22. McIntosh K, Kapikian AZ, Turner HC, Hartley JW, Parrott RH, Chanock RM. Seroepidemiologic studies of coronavirus infection in adults and children. Am J Epidemiol. 1970 Jun;91(6):585-92. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121171. PMID: 4315625; PMCID: PMC7109868.

23. Ma Y, Zhang Y, Liang X, Lou F, Oglesbee M, Krakowka S, Li J. Origin, evolution, and virulence of porcine deltacoronaviruses in the United States. mBio. 2015 Mar 10;6(2):e00064. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00064-15. PMID: 25759498; PMCID: PMC4453528.

24. Sabin AB, Ward R. THE NATURAL HISTORY OF HUMAN POLIOMYELITIS : II. ELIMINATION OF THE VIRUS. J Exp Med. 1941 Nov 30;74(6):519-29. doi: 10.1084/jem.74.6.519. PMID: 19871152; PMCID:

PMC2135210.

25. Drinker P, Shaw LA. AN APPARATUS FOR THE PROLONGED ADMINISTRATION OF ARTIFICIAL RESPIRATION: I. A Design for Adults and Children. J Clin Invest. 1929 Jun;7(2):229-47. doi:

10.1172/JCI100226. PMID: 16693859; PMCID: PMC434785.

26. SABIN AB. Pathogenesis of poliomyelitis; reappraisal in the light of new data. Science. 1956 Jun 29;123(3209):1151-7. doi:0.1126/science.123.3209.1151. PMID: 13337331.

27. Sabin AB. Behaviour of Chimpanzee-avirulent Poliomyelitis Viruses in Experimentally Infected Human Volunteers. Br Med J. 1955 Jul 16;2(4932):160-2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4932.160. PMID: 20788449; PMCID: PMC1980369.

28. SABIN AB. Present status of attenuated live virus poliomyelitis vaccine. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1957 Jan;33(1):17-39. PMID: 13383294; PMCID: PMC1806054.

29. SABIN AB. Oral poliovirus vaccine. Recent results and recommendations for optimum use. R Soc Health J. 1962 Mar-Apr;82:51-9. doi: 10.1177/146642406208200205. PMID: 14495784.

30. LIKAR M, BARTLEY EO, WILSON DC. Observations on the interaction of poliovirus and host cells in vitro. III. The effect of some bacterial metabolites and endotoxins. Br J ExpPathol. 1959 Aug;40(4):391-7. PMID: 14416926; PMCID: PMC2082270

31. Liu J, Liu S, Zhang Z, Lee X, Wu W, Huang Z, Lei Z, Xu W, Chen D, Wu X, Guo Y, Peng L, Lin B, Chong Y, Mou X, Shi M, Lan P, Chen T, Zhao W, Gao Z. Associationbetween the nasopharyngealmicrobiome and metabolome in patients with COVID-19. SynthSystBiotechnol. 2021 Sep;6(3):135-143. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2021.06.002. Epub 2021 Jun 14. PMID: 34151035; PMCID: PMC8200311.

32. Shang C, Liu Z, Zhu Y, Lu J, Ge C, Zhang C, Li N, Jin N, Li Y, Tian M, Li X. SARS-CoV-2 Causes Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Mitophagy Impairment. Front Microbiol. 2022 Jan6;12:780768. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.780768. PMID: 35069483; PMCID: PMC8770829

33. Kohda K, Li X, Soga N, Nagura R, Duerna T, Nakajima S, Nakagawa I, Ito M, Ikeuchi A. An In Vitro Mixed Infection Model With Commensal and Pathogenic Staphylococci for the Exploration of Interspecific Interactions and Their Impacts on Skin Physiology. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021 Sep 16;11:712360. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.712360. PMID: 34604106; PMCID: PMC8481888;

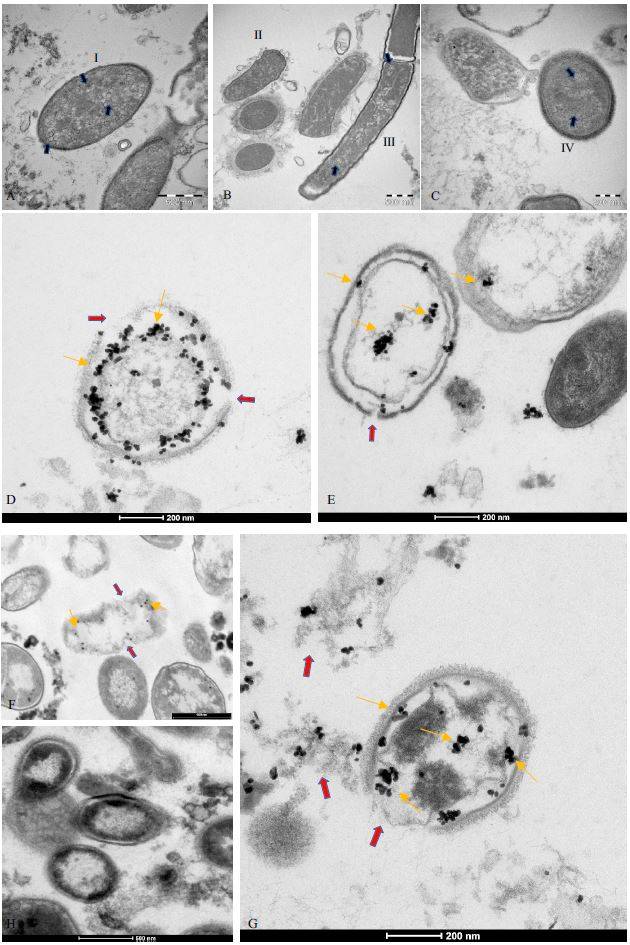

34. KameliN, Borman R, Lpez-Iglesias C, Savelkoul P, Stassen FRM. Characterization of Feces-Derived Bacterial Membrane Vesicles and the Impact of Their Origin on the Inflammatory Response. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021 May 7;11:667987. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.667987. PMID: 34026664; PMCID: PMC8139245.

35. Zhao B, Ni C, Gao R, Wang Y, Yang L, Wei J, Lv T, Liang J, Zhang Q, Xu W, Xie Y, Wang X, Yuan Z, Liang J, Zhang R, Lin X. Recapitulation of SARS-CoV-2 infection and cholangiocyte damage with human liver ductal organoids. Protein Cell. 2020 Oct;11(10):771-775. doi: 10.1007/s13238-020-00718-6. PMID: 32303993; PMCID: PMC7164704.

36. Chen X, Yu L, Steill JD, Oomens J, Polfer NC. Effect of peptide fragment size on the propensity of cyclization in collision-induced dissociation: oligoglycine b(2)-b(8). J AmChemSoc. 2009 Dec 30;131(51):18272-82. doi: 10.1021/ja9030837. PMID: 19947633.